Noyes Academy Part 4

- Feb 7, 2025

- 9 min read

Dueling Rallies and Cognitive Dissonance

In the beginning, the founders of Noyes Academy moved with blazing speed.

Early 1834: The founders assembled an investor group, bought property right next to the new Congregational Church (now the Old North Church); built the school; applied to the state for a charter.

July 4, 1834: Charter granted. In sudden burst of patriotic emotion because it is the Fourth of July and All Men are Created Equal, the proprietors spontaneously decided that this school should accept Black as well as white students. It is unlikely in the extreme that the men of Canaan, just decided on July 4 that admitting Black students was a great idea. Given the large abolitionist presence among the school’s proprietors and trustees, this had to have been the plan from the start.

August 15, 1834: Proprietors of Noyes Academy (proprietors were investors, Noyes was a private enterprise) met in Canaan and formally changed the charter to allow for admission of Black students. Opponents of admitting Black students attended this meeting and agitated for their position, but the proprietors overwhelmingly voted to admit Black students.

September 11, 1834: Noyes Trustees met for the first time in the Academy building. They issued a circular arguing why the school should have wide support.

Each side then held a rally. When Wallace below refers to "anti-slavery" riots, he is means what we would call anti-abolitionist riots. They were only anti-slavery in that they were opposed to any discussion of ending slavery.

Page 253

The nation at this time was at the height of the anti-slavery agitation. During this month anti-slavery riots had taken place in New York City, and had been continued into New Jersey. The people of Canaan sympathized with both sides and the line was as sharply drawn between the abolitionists of Canaan and their opponents as anywhere in the country.

Several abolition orators came to Canaan and served to keep the people stirred on that question, which was not solved for more than twenty-five years after. The friends of the school realized there was going to be a struggle, excitement was in the air; both sides did not hesitate to show their whole strength, and every effort was made to bring it out and place every man either on one side or the other.

Those abolitionist orators Wallace refers to above were here for the abolitionist rally. It was held on September 11 and 12. On the 11th, the school’s trustees (who included not just men from Canaan but some leading lights of the new abolitionist movement) met in the Noyes Academy building for the first time. The result of that meeting was a circular that laid out the case for the school.

They made several arguments in favor admitting Black students. As their first point, they suggest it will be a fair test of whether or not Blacks are educable.

Page 261

We propose to afford colored youth a fair opportunity to show that they are capable, equally with the whites, of improving themselves in every scientific attainment, every social virtue, and every Christian ornament.

If however we are mistaken in supposing, that they possess such capacity; if, as some assert, they are naturally and irremediably stupid, and incorrigibly vicious, then the experiment we propose will prove this fact […]

They go on to point out how very many Black people are living in the U.S. and go on to note that this number can only grow and the enslaved can only come to hate us more. We can’t do nothing and expect things to resolve. The growing number of the enslaved

inspires apprehension in those who are conscious of doing them continual wrong. […]

Next, they indulge in a bit of anti-Irish bigotry, arguing that educating even a few Blacks will pay dividends because those few can control the others the way the Catholic Church controls the Irish.

If, therefore, there really exists between them and the whites, that natural and invincible antipathy, which many allege as an argument against our plan, how important and necessary for the welfare of this whole country that some of their own color should be humanized, christianized and qualified to gain that access to their minds and that control over their evil propensities which upon the above proposition it is impossible for any white ever to acquire.

It is a familiar remark, that it would be an incalculable injury to this country, if the restraint which the influence and instructions of the Catholic Clergy impose, were to be removed from the uneducated and depraved among the Irish emigrants. The total number of those emigrants does not exceed one fifth of the colored Americans!

Thankfully, they return to more high-minded thoughts.

We wish to see him [the Black man or woman] start as fairly as others, unconfined by fetters, unincumbered with burdens and boyaut with hope; and if he shall then fail, we shall at the worst have this consolation, that we have done our utmost to confer upon him those excellent endowments, which the wisdom of God and the solemn appeal of our fathers have taught us to regard as the appropriate distinction of immortal and infinitely improvable beings.

After the trustees meeting broke up, they all trooped next door to the Congregationalist Church where the public was invited to an abolitionist rally. Their opening speaker was a bit of a dud, but it picked up from there.

Page 263

The same day there was a public meeting at the Congregational Meeting House. Rev. Mr. Robbins, a Methodist minister, was invited to open the meeting with prayer. He almost declined, but finally consented. He prayed very cautiously, asking God to bless the enterprise if it was to be for His glory, but as he did not believe it was God’s intention to mix blacks and whites, he prayed that all the efforts might be put to confusion. A careful man, this Robbins, but not honest as God and the law require men to be honest. The meeting was then addressed by Mr. David L. Child of Boston, followed by Samuel E. Sewall of Boston and N. P. Rogers of Plymouth.

That was followed the next day with a speech by Edward Abdy, a British abolitionist who was touring the U.S. at that time, and then another speech by David Child and ending with an address by George Kimball. Let’s note how well planned this was that a famed British abolitionist managed to find his way to tiny Canaan at just the right moment.

And now the cognitive dissonance.

How can the abolitionists be so far from what I want them to have been? They could see the plight of the enslaved, but those degenerate Irish! And George Kimball had a maid Nancy, a woman who had been enslaved by his wife in Bermuda. She was now free. But still in service. And Wallace includes in his book a letter from the great and beloved N.P. Rogers, telling Kimball how lucky he was to have such a great maid, who because of the color of her skin, was essentially unable to leave his service. He was complaining about how often he has just finished training a maid and she up and goes to work for someone else. He asked, teasingly, but still asked, that if Kimball returned to Bermuda, could he pick one up for Rogers just like Nancy.

These are our heroes. They were able to see so much, and they failed to see so much more. I want to go back in time and shake them!

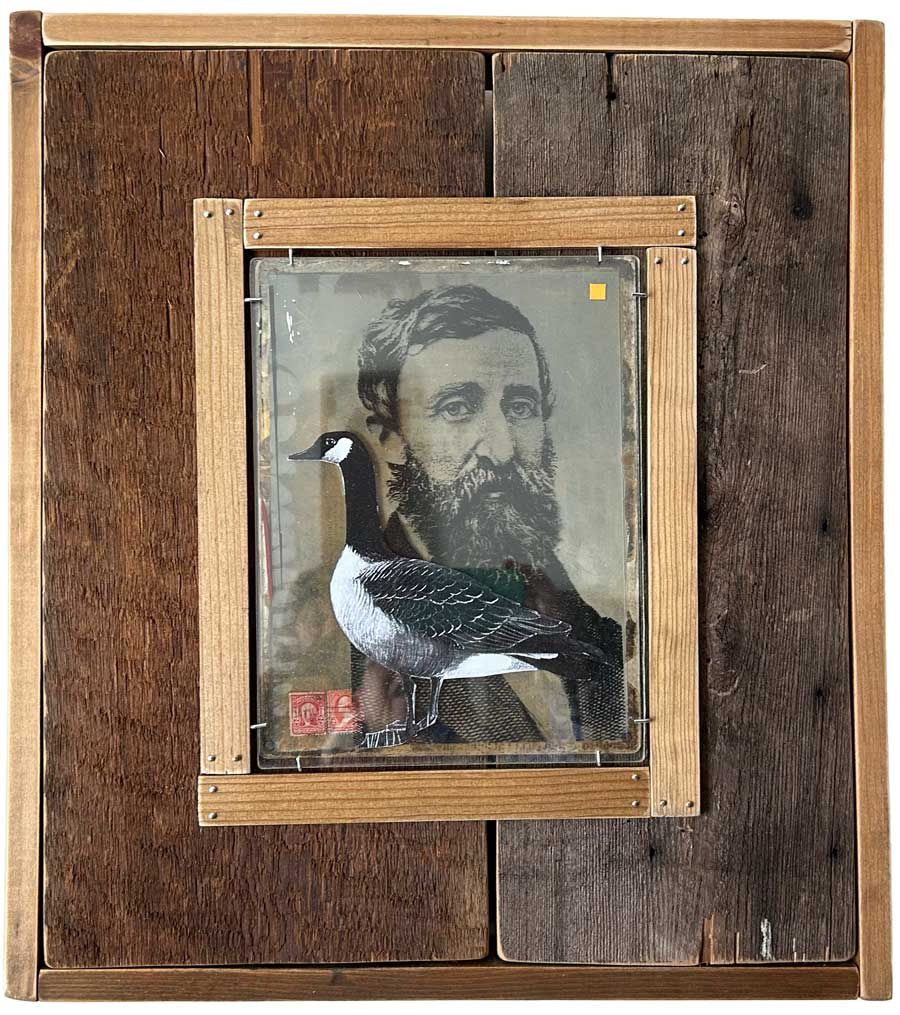

The abolitionists were not the only ones getting their ducks in a row. The opposition had a rally of their own to organize. The cognitive dissonance here is in the lead. There was a lot of discontent about Blacks coming to Canaan, and there was a great deal of genuine sentiment that this country was held together because the North decided to look the other way with regard to slavery. The North knew slavery was bad, they felt bad about it, but they also knew that the economy of the country ran through the South. This allowed people who were creeped out by people whose features were unlike their own to have more principled ground on which to stand. The Union!

Jacob Trussell had a third motivation which was personal. Details in last week’s post. His personal hatred for three of the school’s founders fueled the fire with which he attacked the school.

Page 258

The opponents of the negro part of the plan were not idle. They gathered together in caucus, after the meeting of the proprietors, and decided that a “town meeting” should be called to procure if possible an unfriendly expression from the voting population of the town.

This wasn’t a “town meeting.” It was a rally. And given how violent anti-abolition politics could become, it was a rally the school’s supporters were wise not to attend. They watched from the sidelines to see what would happen.

What happened was that Trussell’s henchman, Elijah Blaisdell (much more about him here) whipped up the crowd. He fed them raw meat about Black men and white women and he fed them patriotism.

Page 260

Great efforts were made to rally the disaffected and to create disaffection. Mr. Blaisdell took hold of the growing sentiment of opposition, petted it, rubbed it the wrong way of the fur, to irritate it, then presented the resolutions, all of which together with his speech, were duly reported in the New Hampshire Patriot.

And, after a lot of bally-hoo, they passed a Resolution!

The resolution starts with a long “whereas” in which they list all the affronts to social order presented by the horror of the school. Below a sample of some overwrought language from this portion of the resolution. Notice that it is but a fragment of a single sentence which began a full half a page before with the word “Whereas.”

Page 259

…not only outraging the feelings of the inhabitants of said town, setting aside the very distinction the God of Nature has made in our species in colour, features, disposition, habits and interests, but inviting every black, who may obtain means by the aid of his own friends and by the aid of a Society heated by Religious and Political zeal, to a degree that would sever the Union for the purpose of emancipation.

This is followed by five statements all of which begin with the word “Resolved.” This is where the cognitive dissonance kicks in hard. Here they are, gathered together for the purpose of keeping Blacks out of town and the first of what will be five Resolveds is about how much they hate slavery.

This seems unexpected. But it was generally the case that New England deplored slavery, in principle. The problem came when they tried to address specifics, i.e., what to do with the millions of enslaved men and women. This is when that “creeped out by Black people” thing comes into play.

Their answer was to ship everyone to Africa (Liberia in specific), a continent most had never seen. But even that was not to happen right away. Right away, they would ship out free Blacks and trouble-making enslaved Blacks. The rest would join them at some future point when it seemed more possible. This went under the name Colonialism. It was the acceptable anti-slavery position, as opposed to Abolitionism which would have actually ended slavery and freed the slaves.

Colonialism was so very effective for the purity of New England. It allowed people to completely deplore slavery, which was so obviously horrid and soul-corrupting, while at the same time profiting from it. You see, they had a completely workable plan to fix this mess once and for all. You just wait and see.

They had Colonialist societies advocating this position. They actually sent some poor men and women to Liberia, a place with no way to support them. They were sent there to die. And for the most part they did.

Their second Resolved was to pity the poor Black men and women suffering under slavery. I can’t even find words to add.

By their third Resolved, they got down to business:

Resolved, that we view with abhorrence the attempt of the Abolitionists to establish a school in this town, for the instruction of the sable sons and daughters of Africanus, in common with our own sons and daughters and that we view with contempt every white man and woman who may have pledged themselves to receive black boarders or to compel their own children to associate with them.

Resolved, that we will not send our children to any Academy or High school, where black children are educated in common with white children, nor in any way knowingly encourage such schools.

Resolved, that we will not associate with nor in any way countenance any man or woman who shall hereafter persist in attempting to establish a school in this town for exclusive education of blacks, or for their education in conjunction with the whites.

So, after all the hoopla, they resolved to deplore slavery but don’t want any Black people in Canaan. This is pretty mild, all things considered. And they only got 86 yes votes. It’s not recorded how many people attended this rally, but there were 300 people on the voting rolls, so the abolitionists, who had not attended at all counted it a raging success. At least half the town was with them!

Winter arrived and the abolitionists were still on fire. George Kimball was all the time back and forth to Boston sending back news of this or that success and sending also Black boys and girls to begin attending the new Noyes Academy.

Comments